In June of 2020, the three hosts of a Catholic radio show were talking about the news of the day.

“I think they should go on ride-alongs, a lot of these bishops,” said Harold Burke-Sivers, a deacon and one of the hosts of Morning Glory. It was a month after the murder of George Floyd, and the U.S. bishops had released a statement condemning police brutality. “I agree that there needs to be reforms. But they should go on ride-alongs and see what these officers do every single day.”

“Amen,” said Vincent De Rosa, another co-host and priest.

“Jesus had 12 apostles, one was Judas, and we focus too much on Judas and not enough on Jesus,” the deacon continued. “Jesus did not reason we should reform the apostles because of what Judas did.”

Gloria Purvis, a layperson and the main host of Morning Glory since it started in 2015, offered a different comparison. “The better example, in my opinion, would be abortion,” Purvis said. “We call for reforms, right?” But the deacon cut in. “Abortion by nature is intrinsically evil,” he said. “Policing is not intrinsic evil.”

“Let me finish,” Purvis said, raising her voice. “Police brutality by nature is evil.”

As a Black Catholic, Purvis had been deeply pained by the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. She was tired, she told me, of hearing about “pro-life” advocacy that didn’t also stand up against the killing of Black people. “They’ll talk about a culture of death, not realizing that racism is very much a part of it,” she said.

Morning Glory was a staple of the Eternal Word Television Network, the world’s largest Catholic media organization. After this exchange among the hosts, the network’s largest radio affiliate pulled the show from air, citing the “awkward and uncomfortable” “spirit of contention.” In the weeks that followed, Purvis received messages from Catholics berating her for talking about racial violence. “A lot of people would write in and say I’m being a critical race theorist and a Marxist,” she recalled. “I had people who were clergy sounding like the most racist public commenters.” But she noticed something consistent: The comments reliably were “the talking points of a political party.”

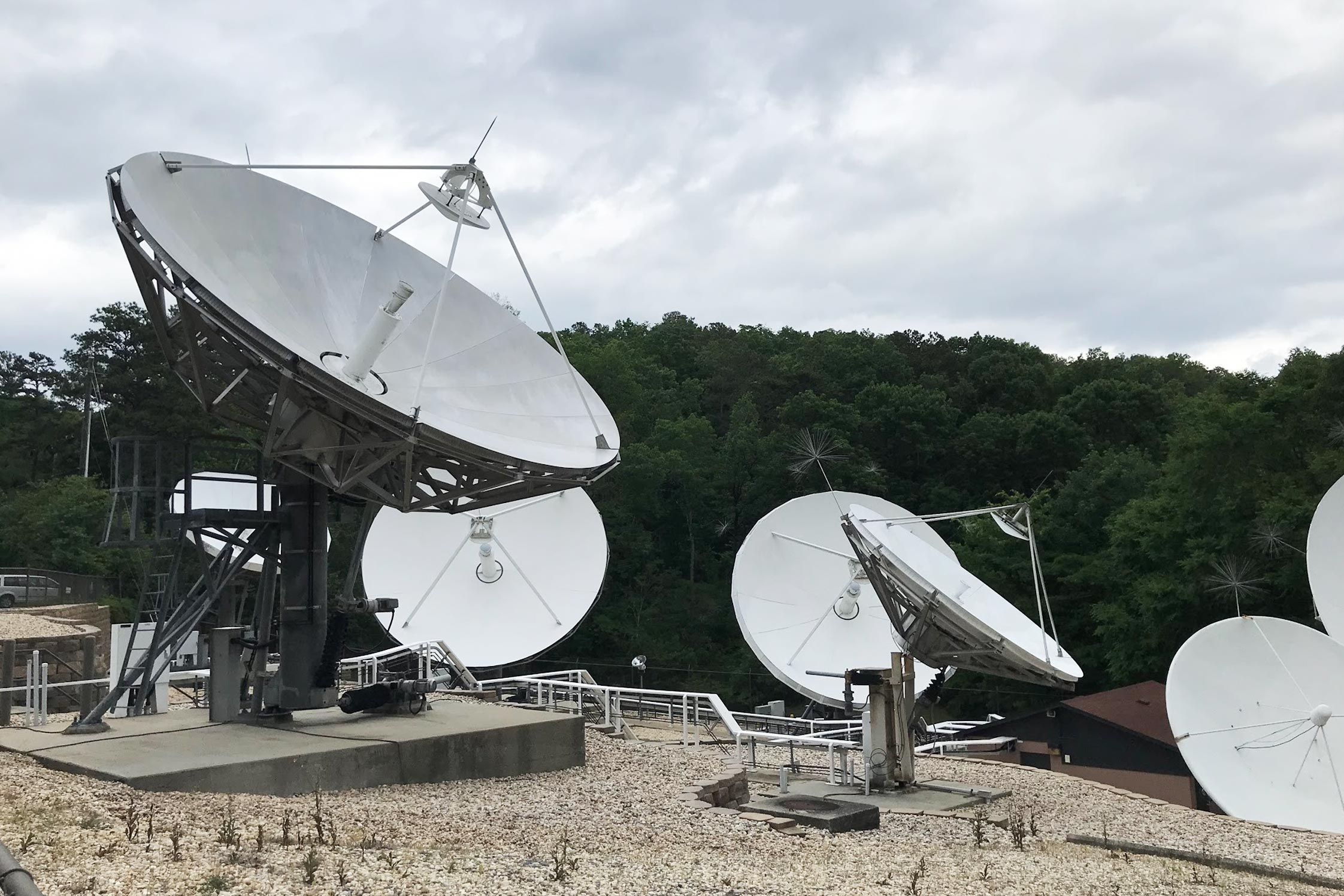

At the end of 2020, EWTN announced that it had canceled Purvis’ show. The move was a surprise only to those who hadn’t watched the network’s transformation over the years. You would be forgiven for never having heard of EWTN, but for millions, it is a towering institution. Founded in the 1980s by a Poor Clare nun cloistered in Alabama, the nonprofit has grown into a media empire, with 24-hour television broadcasting, a network of more than 500 radio affiliates spanning the globe, print and digital news publications, a religious catalog, and a publishing house. Its programming on basic cable and satellite airs in more than 150 countries and in multiple languages, and the network claims to reach nearly 400 million households. A lay-run organization, EWTN answers to no one in the church—not the local bishop, not even the pope.

To many Catholics, EWTN has become the voice of the Catholic Church in America. For most of its 40-year history, this position was largely apolitical. The network’s most popular programs involved the daily Mass, meditations on Scripture, and the recitation of the rosary. Its key demographic was, and remains, devout retirees who tune in for devotional supplements. EWTN claims, in its mission statement, to promote “the advancement of truth as defined by the magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church.”

And you can still find the daily Mass live, if you tune in at 8 a.m. Franciscan friars from an order founded to aid in EWTN’s operations lead the Mass from a chapel at the network’s headquarters in Irondale, Alabama. After that, you can watch the friars pray the rosary, or an educational video on the revelations of Fátima, or a rerun of an old chat by the nun who founded the network. As a receptionist at the headquarters once told me, viewers today call in from all over the world to share the stories of when EWTN’s spiritual guidance pulled them through hard times. Once, she said, a terminally ill woman called in from her room at the Mayo Clinic to say that after discovering EWTN and watching for a week, she had decided she was ready to face her death. During the pandemic, isolated Catholics had tuned in to watch Mass when they could no longer go in person. “I have trouble falling asleep since my husband, Joseph, passed away two years ago,” a 95-year-old woman wrote in a letter published by EWTN’s National Catholic Register. “In January 2021, I scrolled through the television at midnight. I came across your channel and daily Mass. … I am so thankful to have EWTN in my home. It is so hard being alone. You have become my family.”

But something has shifted in EWTN’s programming in the past decade. Instead of seeing a mild-mannered priest in charmingly outdated glasses discussing Eucharistic adoration, viewers might find polished newscasters talking with a string of right-wing figures. On a typical day last month, the evening hours started with a discussion of gun control, Texas’ 28th Congressional District primary, and a sit-down interview with former Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway. Two hours later, after another airing of the daily Mass, this was followed by a show discussing Nancy Pelosi’s right to receive Communion.

This programming, it could be argued, has merely followed the country’s most engaged Catholics as they’ve swung increasingly to the political right over a generation. And it’s a political right that has come into new heights of institutional power along its core issues: abortion, guns, religion. At the same time that conservative secular politics in America have taken a reactionary turn, Pope Francis has steered the church toward a more conciliatory approach to hot-button topics such as divorce and gay rights.

The situation has left viewers facing an uncomfortable truth: The rift between the global church and its American arm has never been wider. Today, as the Catholic world rumbles with talk of schism and dwindling numbers in the pews, EWTN is staging its own proxy war over what it means to be Catholic.

EWTN owes its outsize role in the lives of many American Catholics to the remarkable determination of one woman. Rita Rizzo grew up in Canton, Ohio, during the Great Depression. As a child, according to her official biography, a mysterious and terrifying stomach pain left her bedridden for two years. When she could find no help from medicine, she turned to a mystic in town who spoke to God directly. Rita recovered after nine days of prayer, and in exchange she made good on a deal to dedicate her life to Jesus. At 21, Rita became a cloistered nun, barred from any contact with the outside world.

Mother Angelica—the name Rita eventually took—was a masterful fundraiser. According to her biography, she received special dispensation from her bishop to leave her cloister in order to give speeches and ask for donations to maintain a monastery in Alabama—a monastery she’d founded through a surprisingly successful business making and selling fishing lures. Reporters loved the scrappy nun, and her story was picked up by local and national news. In the ’70s, energized by her success, she spread her faith to laypeople by writing books, taping speeches, and appearing on the radio. But her real calling from God did not become apparent to her until she visited a television station in 1978. With Pat Robertson’s The 700 Club as inspiration, she started filming shows out of a CBS affiliate station, to be aired on the Christian Broadcasting Network. When CBS aired a miniseries based off the popular novel The Word, Angelica was furious over the “blasphemy” of the biblically themed drama and decided to start her own studio. That eventually led to her own network, with a name that referenced both the gospel and a program she sought to condemn. By the mid-’80s, EWTN would become the fastest-growing cable network in the country.

The dynamics of the Catholic Church of the 1980s were somewhat inverted from what they are today. John Paul II, a Cold War–era pope, campaigned against communism and for orthodoxy. American Catholics, meanwhile, were revolting against conservative church teachings on contraception and divorce. That rebelliousness was reflected in the church leadership, too. In 1986, for example, the U.S. bishops published a pastoral letter arguing forcefully against Reagan-style market economics. When a faction of bishops led by New York Cardinal John O’Connor won the support of John Paul by standing firm against condom use during the AIDS epidemic, they were vocally opposed by a frustrated majority. The tension—between the bishops and the Republican Party, and between the bishops and Rome—was hard to ignore.

At the time, these politics mattered little to EWTN. The network’s focus was daily Mass and other liturgical matters. That began to change in 1993. On World Youth Day, a massive church-sponsored event held every few years in a different city around the globe, EWTN had its cameras rolling on Denver’s Mile High Stadium, waiting for a theatrical production of the Stations of the Cross. When a troupe of mimes emerged, dressed in long, white tunics, the figure playing Jesus was revealed to be a woman. On her show the next day, Angelica glared down the camera. “I am so tired of you, liberal church in America,” she said. “You’re sick.” She blasted the American church for disrespecting the pope. “I resent you pushing your anti-Catholic, ungodly ways upon the masses of this country,” she continued. “Don’t pour your poison, your venom, on all the church.” EWTN had a new mission.

The network told the story of Catholicism from one theological perspective. EWTN’s loyalty lay with Rome, not the relatively progressive American bishops, and there were hints that the pope appreciated her efforts; John Paul once told Mother Angelica that she was a “strong woman, courageous woman.” EWTN’s presence continued to grow. As money poured in, Angelica’s empire expanded. EWTN launched foreign-language channels, international affiliates, and a global shortwave radio network. It developed shows for teenagers and other audiences, eventually producing 24 hours a day of original programming. It first moved into news in 1996, with its flagship weekly show, The World Over With Raymond Arroyo.

The shift in the network’s relationship with Rome came in 2013—the same year EWTN launched its nightly news show—when Pope Francis, a reformer with a Latin American worldview, took charge of the Vatican. Since then, the single most common charge critics have leveled against EWTN has been that it is anti-Francis. They have pointed to the network’s cozy relationship with the American Cardinal Raymond Burke, widely considered the leading voice of the Francis opposition. They cited the guests on Arroyo’s show who openly critiqued Francis’ leadership, as well as Arroyo’s own open frustration with Francis’ “laid-back manner.” In those first years of Francis’ papacy, as the Catholic Church underwent an ideological revolution, EWTN made it clear it was not planning to follow suit.

On Easter Sunday in 2016, Mother Angelica died at age 92 after a long illness. She hadn’t been on air since a stroke in 2001, but some still wondered if the network’s days were numbered without her.

Shortly before the 2016 election, Donald Trump sat down with EWTN’s Raymond Arroyo at the Trump National Doral. The host introduced the segment on his show with barely contained delight. He began with a question about Trump’s mother, then turned to the Access Hollywood video, offering the candidate an opportunity to address the criticism. Trump gave his usual answers about “locker room talk,” and from there, the conversation flowed as any Fox News interview might, touching on Obamacare, abortion, and the “rigging” of the electoral process.

Ten minutes into the 15-minute interview, Arroyo seized on Trump’s mention of Hillary Clinton’s emails. “These WikiLeak revelations have offended a lot of evangelicals—and Catholics,” he said. “They suggested that they need to plant seeds of rebellion in the Catholic Church to somehow change the teaching to accommodate their political agenda. They said it was a backward, Middle Age dictatorship.” He wondered aloud if Clinton should apologize.

“Frankly,” Trump answered, “if any Catholic votes for Hillary Clinton—I would say if I were a Catholic, I wouldn’t be talking to them anymore.”

EWTN is often described by critics as the Catholic Fox News. Its coverage of the 2020 election, the inauguration, and the pandemic could easily be mistaken for Fox News with lower-budget sets, unless you stick around long enough to watch a segment on a particular papal blessing. In addition to headlining his own EWTN show, Arroyo is a Fox News contributor, regularly appearing on (and occasionally guest-hosting) The Ingraham Angle, where he rants and jokes about President Joe Biden’s senility or masks or CNN’s obsequiousness. The cadence of his delivery is pulled from the Fox News playbook, but he still feels out of place. With his cheery, clean-cut presence, he has the inescapable air of a grown-up altar boy.

That presence does fit on The World Over, EWTN’s long-running political analysis and interview show. Add in his close ties to Mother Angelica, whose biography he wrote, and it’s understandable that Arroyo has been the face of the network. But not everyone shares his political mission.

“I believe the church is the divine mystical body of Christ, but also a large sociological institution,” a former employee I’ll call Dereck said. (I spoke with more than a dozen current and former employees, and all asked not to use their real names because of the network’s influence in Catholic media. The network did not respond to my request for comment.) “So there’s always a delicate balance. … For all Catholic journalists, left or right, there’s some figuring that out—if you’re trying to do it in good conscience. But if you watch five minutes of Raymond Arroyo, it does not seem to reflect any of that tension. There’s a lot of grappling to do, but not all of the EWTN news programming reflects that.” (Arroyo addressed such criticism on his show in April, saying that “I have never cleared topics or editorial for The World Over with anyone, including donors” and that “people are smart enough to see what’s going on. We have what they do not: It’s called an audience.”)

EWTN has two major bases of operations. Its main headquarters in Alabama, with its quiet leafy setting and squat brick buildings, took over the monastery Angelica founded and still shares a space with friars. In the lobby, a wall of screens shows EWTN’s live programming around the world. The devotional programming is still largely filmed in Alabama, and the network’s leadership oversees the empire from there.

The news operation, where Arroyo works, is based 700 miles away, in a nondescript office in D.C. It has sleeker studios and fewer friars. While the news operation reportedly had some growing pains in its early days as it tried to balance its religious mission with the desire for secular news standards, the political shows have found their rhythm in recent years. EWTN has a fleet of reporters in the Vatican, but it has also beefed up its presence in the U.S. Capitol and at the White House. Starting with the Biden administration’s first White House briefing, an EWTN correspondent has consistently lobbed the press secretary questions about abortion. One former EWTN employee told me that the network was pouring an enormous amount of resources into its news programs.

The guests are one indicator of the kind of news programming EWTN pursues. In recent years, Ben Shapiro has appeared on the network’s pro-life show to give tips on leaving abortion rights advocates “speechless.” A sympathetic Capitol Hill correspondent interviewed Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene about efforts in the House to punish her for inciting violence against Democrats—efforts Greene described as “spiritual warfare.” Arroyo in particular pulls big right-wing names: Sebastian Gorka, Dinesh D’Souza, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, and Ohio Rep. Jim Jordan, among others. Former Vice President Mike Pence once sat down to discuss “media elites and Hollywood liberals.” Most of these guests are not Catholic, but they are all Republican.

The way issues are discussed, even by religious figures, is also reliably Republican. On one episode of EWTN Live, a priest in an armchair on a cozy chapel-like set decried transgender athletes, the “negative history” of the U.S. being taught in schools, and the concept of white privilege. After the shooting in Uvalde, Texas, on May 24, Pope Francis made a direct appeal for gun control: “It is time to say enough to the indiscriminate trafficking of arms,” he said. The next day, Arroyo brought Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, onto his show to discuss the “sociological” reasons behind mass shootings. “It’s not a matter of guns, per se. It’s not a matter of race,” Donohue said. “No gun control is going to stop these men whatsoever. None.” He rejected the idea that the Buffalo shooting was motivated by racism. “This has nothing to do with race,” he said. (In his writings the shooter said he intended to target Black people.) Arroyo nodded his head in agreement.

As former employee Dereck put it: “The universe has shifted, and EWTN has gone along with the far-rightward shift, politically and ecclesiastically.” Another former EWTN journalist, Sophie, put it in personal terms. “Morale was low because we all went in with the expectation that we were working for the church, that we were working for our Catholic faith,” she said. “Not that we were there to provide news with a spin on it.”

That spin can apply to Catholic matters, too. In 2020, the Catholic writer Austen Ivereigh published a book he co-authored with the pope, exploring Francis’ thoughts from the early phase of the pandemic. Ivereigh, who had received the full press tour with EWTN for one of his previous books, was surprised when the network didn’t express any interest in covering its release. “It’s news,” he said. “And yet the biggest Catholic media empire in the world made an editorial decision that the pope should be simply ignored.”

Critics of Francis who appear on EWTN often couch their complaints in matters of “doctrinal confusion”—meaning a turn away from traditionalism and the more black-and-white moral teachings of his predecessors. In a segment in which he also complained about the Vatican’s vaccination policy, Cardinal Burke said that those with a preference for traditional forms of worship were being treated as if “there’s no room at the inn.” The network often lets guests make the more explicit critiques, as when a frequent guest on Arroyo’s show, author Robert Royal, said that Francis’ meeting with Biden “sends a wrong message” about abortion. In that same episode, Royal admonished Francis for his remarks on climate change during the COP26 summit, calling them “hysterical.”

EWTN has also waded into larger disputes in the church. The network broadcast numerous interviews with Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the former papal ambassador who is known for accusing the pope of covering up abuse and calling for his resignation in a fiery 7,000-word letter published through EWTN’s National Catholic Register. Journalists have found little evidence to support the charges, and progressive Catholics have accused Viganò of being a fringe conspiracy theorist trying to oust Francis for ideological reasons. But EWTN’s coverage gave Viganò’s accusations legitimacy, and Viganò remains, in the eyes of many on the Catholic right, an anti-abuse crusader.

Despite this papal coverage, “it’s not completely propaganda,” another former EWTN employee told me. “They’re not going to criticize him outright. But they were more exuberant about Trump than Pope Francis.”

In 2014, a few years after acquiring the National Catholic Register, EWTN also acquired the Catholic News Agency, a service founded to provide Catholic news to media outlets for free. Current and former employees I spoke with said they chafed under the new management’s editorial interference. “We were being waved off stuff that would piss off donors and being accused of disloyalty to the team and mission by raising legitimate criticisms,” one former CNA staffer said. “There were clear limits to what was OK to cover critically.”

EWTN has denied having an anti-Francis bias, and there are loyal EWTN employees who are genuinely stung by the accusation. But according to other former EWTN employees, Ivereigh wasn’t paranoid to think there had been a directive to ignore his work. One reporter who was working at CNA when it was acquired by EWTN told me, “There was a definite change in tone. Some of my stuff would be censored a little bit to imply that Pope Francis didn’t have a Catholic stance on marriage or homosexuality. It just became increasingly controlling.”

Most liberal Catholics agree there is value in viewing the papacy with a critical eye. But given the lack of any real competition for EWTN, critics say there is a danger of the oppositional right being the only voice with a large platform. On May 4, the U.S. bishops announced they would soon close the American offices of the Catholic News Service, the Catholic equivalent of the Associated Press and a competitor to EWTN’s Catholic News Agency. Without it, EWTN’s influence will only grow further.

It’s not a stretch to believe that the Vatican views EWTN as both a necessary tool for reaching the public and a liability, primed to export its reactionary brand of the faith to the rest of the world. According to Christopher Lamb, a reporter for the British Catholic publication the Tablet, several officials in Rome have voiced frustrations with Arroyo’s show The World Over, and someone close to Francis tried to pressure EWTN to fire its host. After years of rumors that the Vatican was unhappy with EWTN’s turn, the pope himself addressed it last fall. During a visit with Jesuits in Slovakia in September, someone asked Francis how he dealt with his critics. “There is, for example, a large Catholic television channel that has no hesitation in continually speaking ill of the pope,” Francis responded. “They are,” Francis continued, “the work of the devil. I have also said this to some of them.”

For many regular Catholics, who don’t know one religious news source from another, EWTN merely matches their understanding of the church as one that takes a firm stance on sexual sins and elevates abortion above all other issues. “There are blog sites and there are networks like EWTN that only teach about abortion, that do not present an entire view of the sanctity of human life and have even been hostile towards the teachings of Pope Francis,” Bishop John Stowe of Lexington, Kentucky, said in an interview with the progressive National Catholic Reporter in January 2021. “That’s not going to help with unity.”

The swerve into partisan politics—to Trump, to Marjorie Taylor Greene, to anti-vaccine nuns—is not as predictable a move as it might seem. Unlike evangelicals, American Catholics did not turn out in large numbers for Trump. In 2016 and again in 2020, exit polls found that voters split almost evenly between the parties. Political analysts have argued that race, education, and other identities tend to determine political affiliation more reliably than religion when it comes to Catholics, and that there is no such thing as the Catholic vote.

So the onset of a clear conservative mission has been disorienting for many of those who have worked for the network. The experience was eye-opening for Purvis, the Morning Glory host who debated police reform with a priest and deacon. EWTN hadn’t just failed to stand up for her when listeners revolted, she said; it had rejected her whole idea of what faith is supposed to be—a driver of justice and compassion.

In interviews, Purvis, who now hosts a podcast for the progressive Jesuit magazine America, was diplomatic and reluctant to directly criticize her former employer. But she was clear about what she thought was missing in EWTN’s partisan zeal. She worried that a spiritual message in the service of politics hardens and narrows into something that cannot encompass the rich diversity of the church’s global community and cannot challenge its faithful as it should.

“What is the purpose of evangelizing,” Purvis said, “if you’re not going to evangelize to the things people are blind about?”