The Altar of the Earth by Michael Ford

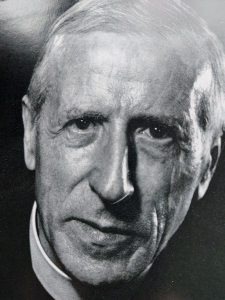

The French mystic and adventurer Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) was renowned for his pioneering work in palaeontology, the study of life on earth through fossils. He was steeped in the evolutionary views of contemporary science but also wrote with lyrical beauty, in such books as Le Milieu Divin, about the real presence of God in the universe.

Teilhard is certainly worth reading at this time of increasing concern for the future of the planet. He was even quoted at the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle in 2018.

It was exactly a century ago, in the summer of 1923, that the Jesuit priest penned the essay “The Mass on the World” during a four-month expedition in northwest China, trekking on the back of a mule. Teilhard initially spoke of the Eucharist as a cosmic offering in his First World War diaries from the front, which is why he began “The Mass on the World” in a particular way:

Since once again, Lord—though this time not in the forest of Aisne but in the steppes of Asia—I have neither bread, nor wine, nor altar, I will raise myself beyond these symbols up to the pure majesty of the real itself; I, your priest, will make the whole earth my altar and on it will offer you all the labors and sufferings of the world.

The slow pace of his exploration through mountains and across desert enabled Teilhard to get in touch with his depths. Sometimes it was possible for him to say Mass en route, but conditions could change and rule this out, so he most likely composed “The Mass on the World” in the tent he shared with a fellow Jesuit, Fr. émile Licent, with whom he had sailed up the Yellow River and dug for fossils. His descriptive powers were always to the fore:

Over there, on the horizon, the sun has just touched with light the outermost fringe of the eastern sky. Once again, beneath this moving sheet of fire, the living surface of the earth wakes and trembles, and once again begins its fearful travail. I will place on my paten, O God, the harvest to be won by this renewal of labor. Into my chalice I shall pour all the sap which is to be pressed out this day from the earth’s fruits.

My paten and my chalice are the depths of a soul laid widely open to all the forces which in a moment will rise up from every corner of the earth and converge upon the Spirit.

“The Mass” celebrates the world as living crucible, the place of divine incarnation and transformation, says Teilhard scholar Ursula King in her biography Spirit of Fire. “It depicts God as energy, fire and power, blazing Spirit moulding every living thing. God is seen as heart of the world, the innermost depth of everything that is. God as milieu in which we live and breathe, and which all is made one.”

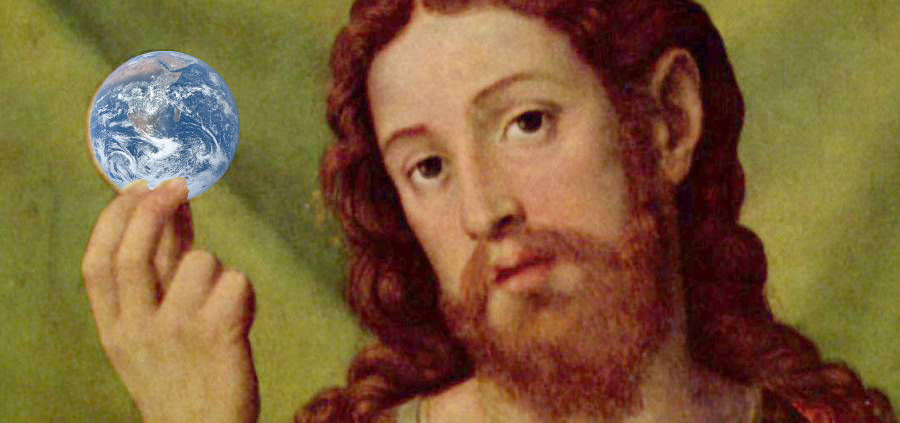

Teilhard is dedicated to one fundamental vision: the union between God and the universe, culminating in the figure of Christ:

Glorious Lord Christ . . . power as implacable as the world and as warm as life; you whose forehead is of the whiteness of snow, whose eyes are of fire, and whose feet are brighter than molten gold; you whose hands imprison the stars; you who are the first and the last, the living and the dead and the risen again; you who gather into your exuberant unity every beauty, every affinity, every energy, every mode of existence; it is you to whom my being cried out with a desire as vast of the universe, “In truth you are my Lord and my God.”

The Cosmic Christ is God’s “incarnate Being in the world of matter.” This is what he prays to, communicates with, and celebrates as the purpose of his being, the all-consuming love of his life. The entire world is God’s body in its fullest extension.

King judges “The Mass” as “an immense cosmic offering, bursting forth like the melodies of a great symphony. The sacred, sacramental nature of the cosmos, symbolized by this offering of the Mass, was for Teilhard an ever-living fountain of renewal for all his life and work.” The words of his “Mass” were always present to him as a living experience.

The essay—published in the 1961 collection Hymn of the Universe—was signed “Ordos 1923.” Ordos refers to people of the Mongolian nation with their own territory and dialect. During his journey across Central Asia, Mongolian and Chinese helpers lent their support.

Teilhard was born in the French Auvergne, and was much influenced by both his aristocratic parents. He was introduced to the Christian mystics by his deeply spiritual mother, while his father, inclined towards natural history, encouraged him to collect bones as well as rocks from the sombre grey stone in the Clermont area of central France. As a young child, he sensed a unifying affinity and later a mystical affiliation with the vast open stretches of sea and desert as well as the intricacies of fossil life. He said he became immersed in God through all of nature.

Teilhard was born in the French Auvergne, and was much influenced by both his aristocratic parents. He was introduced to the Christian mystics by his deeply spiritual mother, while his father, inclined towards natural history, encouraged him to collect bones as well as rocks from the sombre grey stone in the Clermont area of central France. As a young child, he sensed a unifying affinity and later a mystical affiliation with the vast open stretches of sea and desert as well as the intricacies of fossil life. He said he became immersed in God through all of nature.

Educated by the Jesuits, and later teaching at a college in Egypt, he was ordained in 1911 before taking up advanced scientific research in Paris. This study was interrupted when he volunteered to serve as a stretcher-bearer in the trenches during the First World War, mainly with a North African regiment. Though he was later awarded the Military Medal and the Legion of Honor, Teilhard found himself in a liminal space every day on the battlefield, working at the boundary of life and death. War was a crucible of fire forging all his experiences into one powerful vision of God and the world.

The priest saw evolution as holy. He made an absolute commitment in the 1920s to the evolutionary process as the core of his spirituality at a time when other religious thinkers felt such thinking challenged the structure of conventional Christian faith. He pledged himself to what the evidence showed.

Teilhard’s academic distinctions included a professorship in geology at the Catholic Institute of Paris and directorships of the National Geographic Survey of China and the National Research Centre of France. While living in China, Teilhard was a major participant in the discovery and classification of “Peking Man.” During excavations between 1929 and 1937, researchers discovered several partial skulls of the species Homo erectus. The hominids—“Peking Man”—had lived some 400,000 years before.

As well as China, Europe, and America, Teilhard’s scientific career took in several visits to India, Indonesia, Burma, Japan, North and Southern Africa, and South America. After the Second World War, he settled in New York City and worked with the Wenner-Gren Foundation in its commitment to advance anthropological knowledge.

In his later years, Teilhard became preoccupied with the urgent need to develop the spiritual-energy resources required by the human community for sustaining human life and assuring its future. This, he stressed, could only be mastered by the powers of love: “Some day after mastering the wind, the waves, and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of Love, and then for the second time in history we will have discovered Fire.”

Teilhard, who kept a picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus on his desk, believed that God dwelt at the heart of existence, and he saw Jesus as God’s love made manifest. In his writings and private journals, he often refers to “Christ-Omega.” Taking the last letter of the Greek alphabet from Christ’s description of himself in the book of Revelation, he employs it to signify that the risen Christ is the endpoint of the world, the future with a face.

God’s intimate presence or love, burning within his heart, embraces the whole of creation, so all of matter and all of life are touched by the divine. “Love alone is capable of uniting living beings in such a way as to complete and fulfil them, for it alone takes them and joins them by what is deepest in themselves,” Teilhard wrote.

His point, says Teresa White, FCJ, is that all sentient creatures on earth instinctively seek unity and are propelled towards it by the energy of love. “Teilhard is highlighting here the relational character of all reality, and hence the key importance of love in the life of the cosmos and in our own lives,” White explains. “Each act of love, he held, no matter how small or hidden, moves all reality closer to full union.”

During his lifetime, Teilhard was barred by his religious superiors from teaching and publishing his philosophical and religious work, which was considered too unorthodox and dangerous. His manuscripts, bequeathed to a friend, were published posthumously. Books such as The Phenomenon of Man rapidly became bestsellers. According to Robert Faricy, SJ, Teilhard’s ideas “burst like flares in the dark Catholic sky before Vatican II”, later providing the theological framework and main concepts for the influential document Gaudium et spes (“The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World”).

Gravestone of Teilhard de Chardin, Hyde Park, New York

Teilhard is said to have anticipated the eco-theology of Thomas Berry and the creation spirituality of Matthew Fox. Translations of his work into 22 languages have spread his thought into most countries of the world. But, as Ursula King points out, the Jesuit is still far too little known. Writing in her book Christian Mystics a quarter of a century ago, she states: “Many of his views provide strong connections to contemporary discussions about religion and science, ecology and interfaith dialogue, and even bear on aspects of feminism and globalization. He was a daring pioneer of great originality and insight in many fields, although there is also much in his thought that remains undeveloped and open to criticism.”

Teilhard ended his days in residence at the Jesuit Church of St. Ignatius Loyola on Park Avenue in New York City. In March 1955, he told friends he hoped to die on Easter Day. A month later, on April 10—Easter Sunday—during an animated discussion at his personal assistant’s apartment, he suffered a fatal heart attack. He was buried in the cemetery for the New York Province of the Jesuits at the novitiate, then at St. Andrew-on-Hudson in Hyde Park.

Le Milieu Divin, perhaps his best-known work, was first published in French in 1957. The title, which is difficult to translate accurately, was retained for the English edition since the team behind it couldn’t agree on an alternative. Teilhard chose the expression to describe the diffuse presence and influence of God at all levels of created reality in all areas of human experience. God is the central focus, the field of divine energy, from which everything flows, is animated, and is directed. “Le milieu divin” or “the divine mileu” captured the universal influence of Christ through the incarnation of God in the world—in its matter, life, and energy. For Teilhard, the world was sated and vibrant with God. What happened in the world and among its citizens found its culmination in God as its spiritual and divine center.

One of the text’s most moving sequences is a deeply personal prayer in which Teilhard asks God to teach him to treat his death as an act of communion. His words make for a fitting epitaph:

When the signs of age begin to mark my body (and still more when they touch my mind); when the ill that is to diminish me or carry me off strikes from without or is born within me; when the painful moment comes in which I suddenly awaken to the fact that I am ill or growing old; and above all at that last moment when I feel I am losing hold of myself and am absolutely passive within the hands of the great unknown forces that have formed me; in all those dark moments, O God, grant that I may understand that it is You (provided only my faith is strong enough) who are painfully parting the fibres of my being in order to penetrate to the very marrow of my substance and bear me away within Yourself. ♦

Michael Ford may be contacted at hermitagewithin@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!