It is 1987, and CBS News’ Mike Wallace is interviewing Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration Thea Bowman for 60 Minutes.

60 Minutes is a top-rated program, and Wallace, its star, is known for tracking down scammers. He has interviewed everyone from Nancy Reagan to Malcolm X, and his signature trademark is footage of the slammed doors he encounters from wary targets.

For this interview—preserved online—Wallace abandons the intrepid reporter persona. He is smitten by the charismatic African American nun, who brings the dynamism of the Black church into Catholic American settings. She speaks regularly on the gospel with a bent toward the arc of racial justice and reconciliation. Wallace is sitting in a Catholic school classroom, looking oversized on a chair and desk made for children, perusing students’ papers describing how they feel about being Black in Canton, Mississippi. It is only a few decades removed from Jim Crow.

The children are candid: People hate us. They think we look ugly. They say we are still slaves.

Bowman says her mission is to lift up these children, so they see themselves as fully deserving of God’s love.

“Black is beautiful,” she says. She gently prods and cajoles the hard-boiled correspondent and journalistic celebrity. Within minutes, she has Wallace repeating the line: “Black is beautiful.”

Bowman died two years later at age 52. Born Black in a segregated world, she inspired not only Catholic schoolchildren but also her community of sisters. She taught in parochial schools and at Xavier University of Louisiana and spoke and sang at faith meetings, including a national bishops’ conference just before her death.

In 2022, just two years after the massive reckoning with racial justice the United States faced after the murder of George Floyd, Bowman is being invoked as a saint for our time. On the first rung of the canonization ladder, she is now a Servant of God. Interest in her cause indicates how candidates for canonization are often seen as much as a product of the time in which they are promoted as well as of the time in which they lived.

Bowman’s long campaign against racism—always delivered with an inspiring message and rooted in the gospels—could make her the first African American designated as a saint by the Catholic Church. She could be a saint for our time, as the 2020s may be even more divisive than her own.

She would always insist “Black is beautiful,” a forerunner of the current “Black lives matter,” a phrase finding an uneasy reception in some U.S. Catholic quarters. Bishop Robert J. McManus of the Diocese of Worcester, Massachusetts, for one, told a Jesuit middle school to take down a Black Lives Matter banner and a rainbow LGBTQ flag because, he said, both symbolize divisive and anti-Catholic points of view. When the school refused, the bishop proclaimed it could no longer be considered a Catholic institution.

Kathleen Sprows Cummings, a historian at the University of Notre Dame, notes that the laborious road to canonization is filled with the concerns of those who promote saint causes. There are national patron saints—France’s Joan of Arc, for example—and there are saints whose canonization causes forge ahead in response to contemporary issues.

One example of the latter is that of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American-born saint, whose cause was championed beginning in 1907 by American Catholic bishops concerned about anti-Catholicism. The suspicion was that Catholics were not true Americans, and Catholics bore the brunt of various forms of discrimination. St. Elizabeth, a convert who is credited with developing the Catholic school system, was the bishops’ answer. She emerged from a prominent colonial American family, and her bona fides as an American could not be disputed. She was eventually canonized in 1975, more than a decade after the election of the first Catholic president.

Today may well be different, says Sprows Cummings, who has written extensively on the sainthood process.

“We are more polarized now,” she says.

Making saints has often been the province of religious orders. There are financial costs involved, but perhaps more important is the need for long-term stick-to-it-iveness. It can take decades for a holy person to move from blessed to sainthood. It takes organization, dedication, and patience.

Nearly all groups have their heroes, people looked upon as extolling vital virtues. But none take heroic virtues as seriously as the Catholic Church, which selects its formal saints through an arduous canonization process, including levels of Servant of God, Venerable, Blessed, and then canonization, complete with proof of miraculous healings. Sainthood causes promoted among American Catholics today reveal the longing for a renewed church, related to heaven above while rooted in contemporary realities.

Bowman’s cause is among an assortment being advanced for Black American saints. It comes at a time when Black Catholics in the United States are on the decline, according to a Pew Research study. Only 4 percent of American Catholics are Black, and an increasing number of those are born outside the United States, from Africa and the Caribbean.

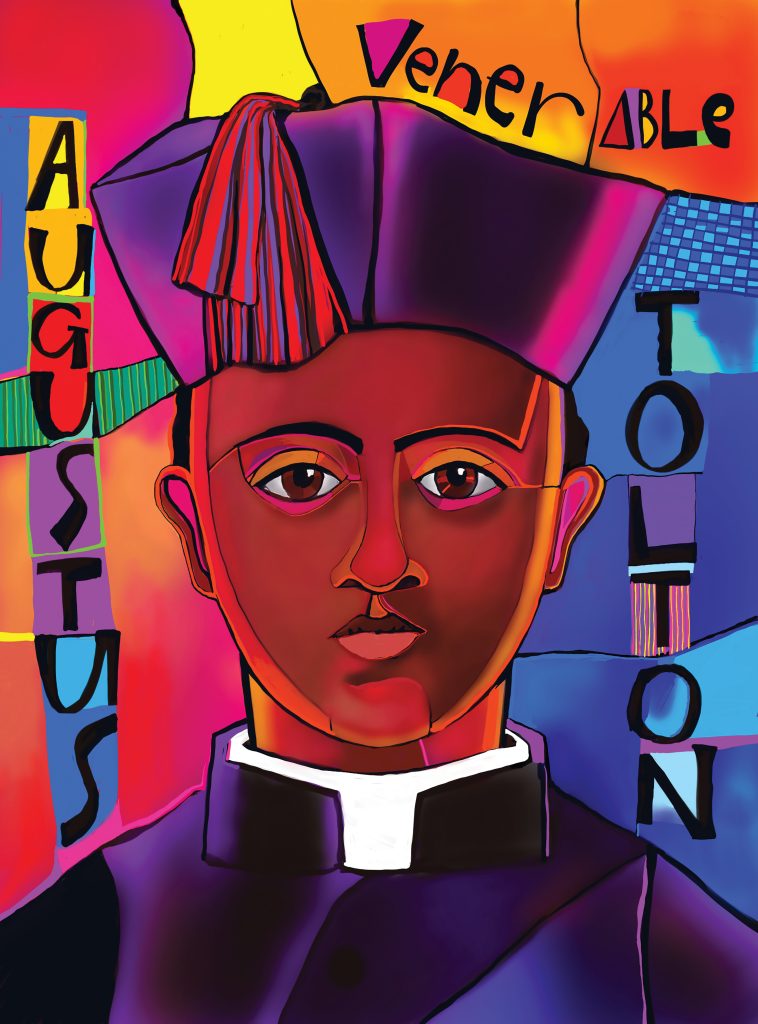

The tradition of Black American Catholicism lives on in various sainthood causes. Potential Black American saints include Julia Greeley, a 19th-century laywoman, born enslaved, known for her quiet outreach to the poor of Denver; Pierre Toussaint, an enslaved Haitian and professional hairdresser, known for his charity in 19th-century New York City; and Father Augustus Tolton, the first recognized Black American priest, who pastored churches in Quincy, Illinois and Chicago after the Civil War.

The Black Catholics being considered for sainthood are not simply for African Americans. Bowman, for one, was a popular galvanizing lecturer on the Catholic circuit, speaking to both Black and white Catholics. Tolton’s cause received a boost when the late Cardinal Francis George of the Archdiocese of Chicago cited him as a model for all clergy during the Year of the Priest in 2009. Tolton is often cited as a man of determined faith, who pursued priesthood and pastoral ministry despite racist snubs from every American diocese he approached, forcing him to go to Rome for his studies and ordination.

Meanwhile, other local causes continue to emerge, bucking the odds that formal canonization remains largely the province of priests and religious.

One such cause is that of Irving C. Houle, promoted in the Diocese of Marquette in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Houle, who died in 2009, in many ways fits the profile of a traditional saint: He is said to have suffered the stigmata, the wounds of Christ in his hands, and was known for intense piety.

He was a husband and father, a World War II veteran, and a member of the Knights of Columbus. He became locally famous for blessings and healings in charismatic prayer services, including praying with players and fans at high school football games.

People would come from all over the upper Midwest to receive his healing blessings, sometimes to the chagrin of local clergy. Houle would always seek ecclesial permission and was, by all accounts, a traditional Catholic. But he was willing to perform blessings and pray publicly, actions reserved in many Catholic circles to the clergy.

“It was a powerful thing to witness,” says Deacon Mike LeBeau, a promoter of Houle’s cause for the diocese. “He was a saint of our time.”

LeBeau notes that the cause has collected 175 testimonials attesting to the power of Houle’s healing, which Houle always attributed to a higher power.

“I pray for you. But Jesus is the one who heals you,” Houle would say regularly.

While Houle was well known in Catholic circles in Upper Michigan, Franciscan Father Mychal Judge burst onto international consciousness when he became the first recognized fatality of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center. Judge, a chaplain for the New York City Fire Department, became renowned in death through a photograph taken soon after the attack, depicting him as a kind of modern pietà, his body stretched out and held by firefighters as the Twin Towers collapsed.

A cry that Judge be considered for sainthood arose almost immediately as his story became identified with that of the firefighters and police officers who entered the World Trade Center as rescuers and perished. Soon the stories of the living Judge emerged, including his generosity to many down on their luck and his support for those in 12-step programs. It also became known that Judge acknowledged himself as gay, causing consternation in some Catholic circles.

But that is changing, says Francis DeBernardo, executive director of New Ways Ministry, an outreach to LGBTQ Catholics, and a biographer of Judge. Five years ago, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints asked New Ways Ministry to gather material on Judge’s life. The cause was bolstered when Pope Francis added another consideration to sainthood, someone who dies in service to others, even if it is not a religious martyrdom. Judge’s death fit that category.

“The problem is it costs a lot of money and takes a lot of time and work to get a cause promoted,” says DeBernardo. New Ways Ministry is seeking potential supporters.

Judge’s sexual orientation is a part of his life that should be considered in the sainthood calculus, says DeBernardo. Judge ministered at a Dignity New York chapter, a support group for gay Catholics, and worked with HIV/AIDS patients. While not everyone knew he was part of the LGBTQ community—after his death, some police officers and firefighters argued that he was being maligned by the association—Judge let it be known that he identified as gay, says DeBernardo, though he only made that revelation to those he felt were ready for it.

Judge could be seen as a potential patron for LGBTQ Catholics, says his biographer.

There are no known gay saints. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t LGBTQ saints, says DeBernardo. One factor working against such recognition, besides church teaching, is that gay culture is a relatively modern phenomenon. There are saints whose writings express deep same-sex friendships—the famous British cleric Cardinal John Henry Newman is one—but they lived in times before a subculture welcoming to gay people was recognized. And, some argue, the sometimes flowery language of other centuries should not be interpreted in a sexualized modern way.

DeBernardo argues that Judge, who as a gay man of modern times struggled with church teaching and identity issues, could be a role model.

“LGBTQ people would see him as one of their own. They recognize the same struggles every LGBTQ person has, in particular the struggle about how public to be,” says DeBernardo. “Because he struggled with it, it makes him more of a candidate to be a gay saint. He shared the same struggles that everyone in the community does. Holiness and a gay identity are not only complementary, they are often integral to each other.”

DeBernardo also sees Judge as an inspiration beyond the LGBTQ community. Judge deeply identified with firefighters and worked with recovering alcoholics, a group he personally identified with.

If Judge could be seen as a kind of patron for firefighters, so could Julia Greeley. She would wander through the frontier town of 19th-century Denver, dropping off prayer cards of the Sacred Heart of Jesus at fire stations. What we know about Greeley are largely snippets about her life. Born enslaved in Missouri, Greeley lived into her 80s and died in 1918, but little survives to record her life spent as a domestic worker on the frontier.

The record that does exist recounts that she lost an eye when a lashing landed on her face, the result of a whipping directed at her mother. The only surviving photo of her is one of her holding a white infant, whom she told a Catholic couple she worked for to expect after the death of their previous child. She was known around town for pulling a little red wagon filled with baked goods. She would unobtrusively drop them off at night for struggling families, due to her humility or a desire not to embarrass poor white families, who could be ostracized for accepting help from a Black female domestic worker.

Greeley, whose cause is championed by the Archdiocese of Denver, could be the first Black American saint. Deacon Clarence McDavid, who has researched her life and advocates her cause, emphasizes that her appeal transcends racial identity.

“I see her as a model for Catholics. It doesn’t matter if you are Black or white,” he says.

McDavid marvels at the impact of Greeley who, after her death, was mourned by thousands of Denver residents, the rich and poor of all races and religious backgrounds. Her funeral attracted the notice of the local newspaper. “She grew up at a time when there was a rigid class structure. Not everyone was going to accept a poor Black woman,” he says.

Another Black American canonization candidate is Father Augustus Tolton, the first openly Black American priest. He was born in 1854 and died in 1897. Tolton pastored churches in the then Diocese of Alton, Illinois and the Archdiocese of Chicago. He spoke around the country spreading the message that Black people should look to the Catholic Church as a sign of universal Christianity, citing African saints such as Augustine and Benedict the Moor.

While a champion of the Catholic cause, Tolton himself found his spiritual path a difficult one, as he experienced racism among his fellow Catholics. Because of his race, he was refused ordination in the United States and was forced to study in Rome. Father Daren Zehnle of the Diocese of Springfield, Illinois was among those leading a procession in Tolton’s honor in the summer of 2022 at the 125th anniversary of his death.

Tolton is seen as a champion of Black Catholics but also as an emblem of the priesthood, says Zehnle. “When the church looks to saints, it doesn’t look for the color of their skin,” he says. Zehnle wrote his undergraduate thesis on Tolton and sees him as someone who saw the priesthood as a valuable gift, overcoming racism in his pursuit of ordination and ministry.

Other contemporary saint causes offer encouragement to Catholics who are part of groups that have experienced a decline in religious practice.

Michelle Duppong died of cancer at age 31 on Christmas Day in 2015, a year after her diagnosis. Those who knew her saw her as a model of a practicing, faithful Catholic among a generation seen as frequently abandoning formal religious practice. Duppong worked as a Fellowship of Catholic University Students (FOCUS) missionary on campuses and, at the time of her death, was director of adult faith formation for the Diocese of Bismarck, North Dakota.

Duppong’s friends describe her as a woman inspired by faith. She was raised on a North Dakota farm and earned a degree in horticulture at North Dakota State University. When she led college students on a mission trip to New York City—a first such visit for many in the group—she navigated them through the subway system, even as they waited for a late-night train that never came, with a serenity that inspired those around her.

She confronted terminal illness with faith. “She was a light of inspiration for those who cared for her,” says Msgr. James Patrick Shea, president of the University of Mary in Bismarck, an institution where Duppong served as a campus minister. Her cause has been taken up by the Diocese of Bismarck, and Shea says she serves as an inspiration for young Catholics. He says he was struck by her trust that faith could overcome obstacles.

Duppong’s cause has developed around her local community, an example of how a faith-filled person can inspire others around them. The canonization process is based upon an informal consensus, which is then ratified by the wider church. The process has a long history.

“In a way it is a return to a tradition in the church. Saints were proclaimed by the local community,” notes Sprows Cummings. Local bishops, not Rome, were charged with canonizing worthy candidates until that task was moved to Rome in the 17th century.

If today’s church in the United States lacks saints to address contemporary issues, it’s not for lack of trying.

Bowman’s cause in particular seems to have emerged at a turning point in American history. As Wallace described her back in 1987, her message was one tinged with social justice, a “new Black Catholic Gospel, powered by the conviction that when something is wrong, you change it.” He described her talks to integrated audiences, complete with singing and dancing, as ways “to literally put the races in touch with each other.” Some see that message as particularly pertinent to a polarized society. Bishop Joseph R. Kopacz of the Diocese of Jackson, Mississippi, which is championing Bowman’s cause, says she “speaks to who we are and who we want to be.”

Besides African American saint possibilities, other groups are also raising up potential sainthood champions. Dorothy Day’s cause has been championed by the Archdiocese of New York, and her life is seen as a model for social justice activists. Notre Dame de Namur Sister Dorothy Stang, a missionary born in Dayton, Ohio and murdered in 2005 after she protested against the land use practices of wealthy Brazilian landowners, is seen by some as a champion of Catholic environmentalism. And Black Elk, of the Lakota people, lived in the 19th century and is being promoted by the Diocese of Rapid City, South Dakota as a model of Christian piety and fidelity to Native American spirituality.

But none of the saints with open causes can be defined simply as special-interest pleading. Each offers more than an ethnic or cultural identity. Francis of Assisi, for one, is the patron saint of Italy, but he has been enshrined by his devotees in a way that transcends a single nation. He is better known as a universal symbol for all God’s creation, invoked when Catholics and others seek blessings for their pets and when they express love for the environment.

So it is for those Americans being considered for sainthood today.

“Sainthood begins with people clamoring for a specific person,” says DeBernardo. “Saints are always saints for identity. But they should also be those whose lives can be imitated universally.”

This article also appears in the November 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 11, pages 24-29). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All art © Brother Michael O’Neill McGrath, O.S.F.S.

Header image: Sister Thea Bowman and Dorothy Day

Add comment